Importance of Transactional Analysis to Recruiter

The recruiter interacts primarily with

To transact effectively with every applicant, the recruiter needs to understand oneself and understand the characteristics or behavior of the applicant and the hiring manager.

To help the recruiter prepare for this role, the recruiter must become conscious that the recruitment is an enabling function and the recruiter is an enabler.

The applicant and the hiring manager have the right to refuse any opportunity or an applicant, respectively. The recruiter can be left high and dry between the choices made by the applicant and the hiring manager.

The recruiter must be constantly alert and try to effectively deal with the applicant and the hiring manager proactively, keeping in mind the negative outcomes that can continuously arise due to the choices made by the applicant and the hiring organization.

During the recruitment cycle, the recruiter must be aware.

The recruiter must be equally aware that there is likely to be noise in the system owing to the unpredictable choices made by the applicant and the hiring manager.

Since the recruiter is the enabler, the recruiter will be held accountable for recruitment irrespective of the choices made by the applicant and the hiring manager.

There are two sets of actions that can be taken.

This section focuses on the proactive aspect discussed above:

While each applicant is a new prospect and an unknown quantity, the hiring manager is a relative constant, whom the recruiter gets to interact and know over a period of time.

The recruiter is enabling the activity and at all times must consider oneself as an equal with the applicant and the hiring manager.

Every time the recruiter is dealing with a new applicant, it is imperative that the recruiter assess the behavioral characteristics of the applicant to transact with the applicant effectively.

The recruiter must also be conscious that they often interact with the applicant on the phone and may not understand the applicant's body language on the other side of the phone.

The ability to understand the characteristics of an applicant or hiring manager in combination with knowledge of the recruiter’s own behavioral characteristics can help the recruiter develop a strategy to transact effectively.

In this context, please find three sections on Transactional Analysis.

Analysis of self

Constantly improving one's understanding of oneself is important in interpersonal communication. The Johari window helps individuals improve their knowledge of self concerning interpersonal communication.

The Johari window is a technique created by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955 which can be applied to help people better understand their relationship with self and others.

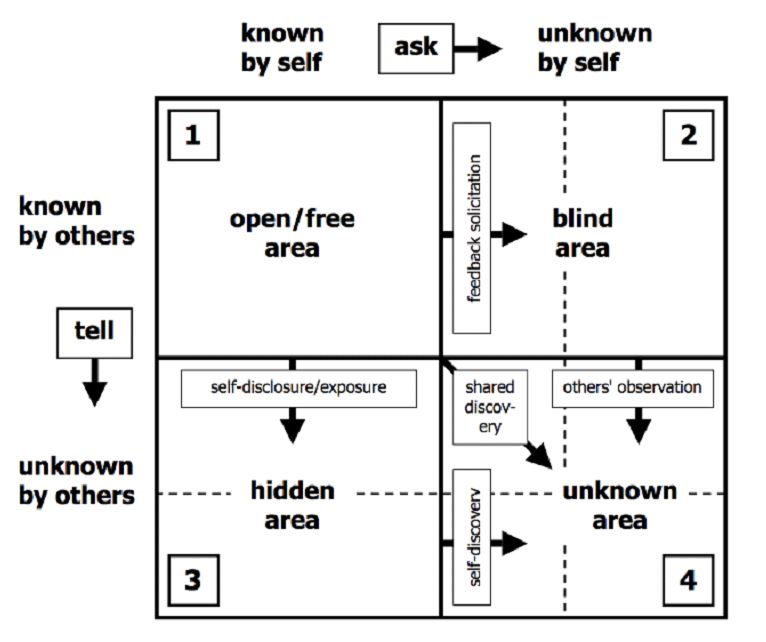

Look at the model below as a communication window through which you give and receive information about yourself and others. Look at the four panes in terms of columns and rows. The two columns represent the self; the two rows represent the group. Column one contains "things that I know about myself;" column two contains "things that I do not know about myself." The information in these rows and columns moves from one pane to another, as the level of mutual trust and the exchange of feedback varies in the group. As a consequence of this movement, the size and shape of the panes within the window will vary.

The first pane, the "Arena," contains things that I know about myself and about which the group knows. This window is characterized by free and open exchanges of information between me and others; this behavior is public and available to everyone. The Arena increases in size as the level of trust increases between individuals or between an individual and the group. Individuals share more information, particularly personally relevant information.

The second pane, the "Blind Spot," contains information that I do not know about myself but the group may know. As I begin to participate in the group, I am not aware of the information I communicate to the group. The people in the group learn this information from my verbal cues, mannerisms, the way I say things, or the style in which I relate to others. For instance, I may not know that I always look away from a person when I talk or that I always clear my throat just before I say something. The group learns this from me.

Pane three, the "Facade" or "Hidden Area," contains information that I know about myself but the group does not know. I keep these things hidden from them. I may fear that if the group knew my feelings, perceptions, and opinions about the group or the individuals in the group, they might reject, attack, or hurt me. As a consequence, I withhold this information. Before taking the risk of telling the group something, I must know there are supportive elements in our group. I want group members to judge me positively when I reveal my feelings, thoughts, and reactions. I must admit something of myself to find out how members will react. On the other hand, I may keep certain information to myself to manipulate or control others.

The fourth and last pane, the "Unknown," contains things neither the group nor I know about me. I may never become aware of material buried far below the surface in my unconscious area. However, the group and I may learn other material through a feedback exchange among us. This unknown area represents intrapersonal dynamics, early childhood memories, latent potentialities, and unrecognized resources. The internal boundaries of this pane change depending on the amount of feedback sought and received. Knowing all about myself is extremely unlikely, and the unknown extension in the model represents the part of me that will always remain unknown (the unconscious in Freudian terms).

The main objective of the model is to increase mutual understanding that encourages disclosure and feedback. This increases our open area so that you and your colleagues are aware of your perceptual limitations. This, in turn, reduces the blind, hidden, and the unknown areas through disclosure, i.e., informing others of your beliefs, feelings, and experiences that may influence the work relationships. The open area also increases through feedback from others about your behavior, which sounds easy but very difficult to seek. However, this kind of feedback will invariably help you reduce your blind area because your coworkers often see things in you that you cannot see for yourself. And finally, the combination of disclosure and feedback occasionally produces revelations about information in the unknown area.

Ego-states

It represents a person's way of thinking, feeling, and behaving. There are three ego states present in everyone: child, parent, and adult. They are related to the behavior of a person and not their age. They are present in every person in varying degrees. When two persons communicate with each other, communication is affected by their ego states.

These are;

Child ego

Child behaviour reflects a person's response to communicate in the form of joy, sorrow, frustration, or curiosity. These are the natural feelings that people learn as children. It reflects immediate action and immediate satisfaction. It reflects the childhood experience of a person generally gained up to the age of five years.

A child can be:

Parent Ego

Parent behavior is acquired through the external environment. As young children, their parents' behavior remains embedded in their minds, reflected as the parental ego when they grow up. It usually reflects protection, displeasure, reference to rules, and work based on past precedents.

A parent ego can be:

Adult ego

This state evokes logical, reasonable, rational, and unemotional behavior. Behavior from the adult ego state is characterized by problem-solving analysis and sound decision-making. People operating from the adult ego state are taking emotional content of their child ego state, the value-laden range of their parent ego state, and checking them out in the reality of the external world. These people are examining alternatives, probabilities, and values prior to engaging in a behavior.

Analysis of transactions

TA may be used to explain why people behave in specific patterns throughout their life. This analysis enables people to identify patterns of transactions between themselves and others. Ultimately, this can help us determine which ego state most heavily influences our behavior and the behavior of other people we interact with.

Developing our understanding of two types of transactions would help us become better communicators.

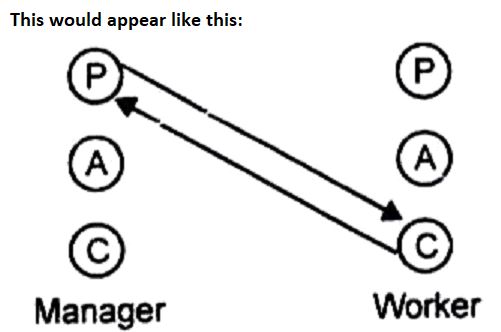

Complementary /open transactions

There can be nine combinations of Complementary /open transactions;

adult – adult; Parent – parent; child – child

adult – parent; Parent-child; child–parent

adult – child; Parent – adult; child – adult

The basic principle is that the ego state should get an appropriate response to continuing the transaction. Communication can continue when a response to a transaction is from an expected and predictable ego state. However

Non Complementary /Crossed transactions

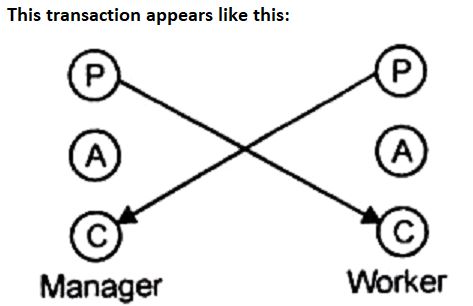

A crossed transaction results in the closing, at least temporarily, of communication. In crossed transactions, the response is either inappropriate or unexpected. It is also out of context with what the sender of the stimulus had initially intended. This occurs when a person responds with an ego state different from the one the other person was addressing. In other words, it occurs when the stimulus from one ego state to another ego state, such that the sender feels misunderstood, confused, or even threatened; when this occurs, sharing and listening stop at least temporarily.

For example, a manager says to his employee, "you misbehaved with your colleague yesterday, and I don't expect this behavior to be repeated." The communication represents the manager's parent ego and the worker's child ego. Rather than being apologetic, the worker responds, "I did not do anything wrong. I shall not make apologies."

This is an unexpected behavior were the parent of the worker talks to the child of the manager.

When the parent ego of the manager talks to the child ego of the worker and the child ego of the worker talks back to the parent ego of the manager, communication is effective, but where egos get crossed, communication breakdown takes place. For example, the above interaction between manager and worker would have been effective if the worker had said, "I am sorry, sir, I'll take care not to behave like this again."

By proper understanding of one's own ego state and that of the other, communication barriers on account of behavioral maladjustments can be reduced. Transaction Analysis transforms negative attitudes of people into positive attitudes. It changes failure, fear, and defeat to victory, optimism, and courage. It makes people strong and directed towards positive thinking.

It improves interpersonal relationships amongst people by understanding their ego states. Crossed transactions can be converted into complementary transactions, and communication process can be improved. People will be more comfortable interacting with each other. This will enhance the effectiveness of the organization.

Life Positions

A person's behavior depends upon his experience at different stages of his life. Therefore, he develops a philosophy towards work from early childhood, which becomes part of his identity and remains with him for a lifetime unless some external factor changes it. These positions are called lifetime positions.

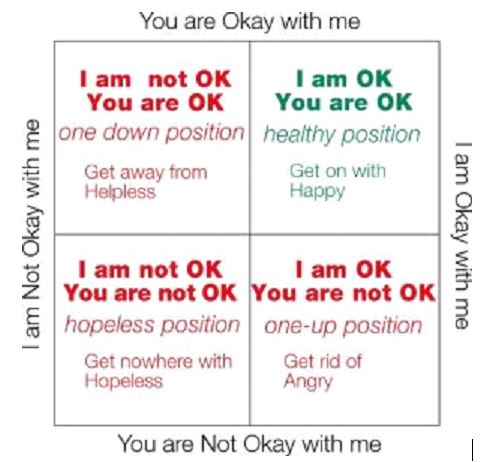

Eric Berne initiated the principle within Transactional Analysis that we are all born 'OK' — in other words, good and worthy. Frank Ernst developed these into the OK matrix.

The OK-not OK Matrix

I’m not OK – You’re OK

When I think I'm not OK, but you are OK, then I am putting myself in an inferior position to you. This position may come from being belittled as a child, perhaps from dominant parents, careless teachers, or bullying peers. People in this position have low self-esteem and will put others before them. They may thus have a strong 'Please Others' driver.

I’m OK – You’re not OK

People in this position feel superior in some way to others, who are seen as inferior and not OK. As a result, they may be contemptuous and quick to anger. Their talk about others will be smug and supercilious, contrasting their own relative perfection with the limitation of others. This position is a trap into which many managers, parents, and others in authority fall, assuming that their given position makes them better and, by implication, others are not OK.

I’m OK – You’re OK

When I consider myself OK and frame others as OK, there is no position for me or you to be inferior or superior. This is, in many ways, the ideal position. Here, the person is comfortable with other people and with themselves. They are confident, happy, and get on with other people even when there are points of disagreement.

I’m not OK – You’re not OK

This is a relatively rare position, but it perhaps occurs when people unsuccessfully try to project their bad objects onto others. As a result, they feel bad while also perceiving others as bad. This position could also result from relationships with dominant others where the other people are viewed with a sense of betrayal and retribution. This may later get generalized from the bullies to all other people

REFERENCES

https://www.crowe-associates.co.uk/psychotherapy/transactional-analysis/